Skyline’s African American Humanities class has been an elective class in the district for over a decade. With its unique take on learning and student engagement, it is both a collaborative and research-based class.

The purpose of the class is to understand the true history of African American ancestors and to provide a space where students can feel included. Some topics the class covers include race, identity, civil rights, and the Great Migration. Co-teachers Tonya Whitehorn and Kathy Mackercher agreed to give their perspective on the history and intentions of the class. The co-founder of the class, Kay Wade has also given her input on the beginnings of the class at Huron High School.

What is the history of the AAH class and who started the class? Why was it started?

Wade: “The African-American Humanities was created at Huron High School by teachers Krystal Hall Abney and Kay Wade. The course was designed to validate the experiences of African-Americans through understanding US history and American literature from an African American Perspective. The course was deliberately designed to be more challenging by developing a critical eye with which to examine the world while working to create new knowledge. Another goal was to encourage African-American students to develop the confidence to take accelerated and AP courses in which they are under-represented. We had to go before the district curriculum committee to get the course approved for an AC designation. The original course at Huron included Afrocentric Psychology lectures taught by Dr. Byron Douglas, an Ann Arbor School Psychologist, and an added dance element taught by Robin Wilson, a dance professor at the University of Michigan. We included both at Skyline and it continues today.”

Whitehorn: “Kay Wade…was the catalyst for the African American Humanities Course. She felt that students of color needed a choice that was accelerated. Learning about one’s history in a class where you could earn AC credit – it hadn’t been done before in the district. She wrote the curriculum with another teacher. The class is taught in two blocks – a history and a literature portion. Once Ms. Wade started at Skyline she taught the history portion and asked me to teach the literature portion of the class. Kathy Mackercher was the support in the class, so for the first time we had an accelerated course that had a teacher consultant component that was working in special education in an accelerated course. We were the grand experiment because we were an accelerated class with teacher support…we filled that need.

Mckercher: They [Ms. Wade and Ms. Hall-Abney] were able to collaborate with Eastern Michigan University and the University of Michigan with the support of [dance teacher Robin Wilson]. And so this conglomeration became a really positive experience and so that’s how it started. From my conversations with Kay and from student feedback was that the US history curriculum is often not diverse honestly and it focuses on white writers, white artists and people in history who were making history textbooks that students are reading. Also, [we wanted] to build a community and to educate people more [about] that there is more to this country than one way of thinking, one way of doing, and one way of being.

What types of topics do you cover in the class?

Mackercher: In the beginning of the course, we start with identity and self exploration. For example we ask the student questions to put themselves in the context of their learning. How do we define race and how do we have conversations about race constructively? The opening assignments of the course are very self-reflective about the role of race in their own lives and that we start to share our stories and perspectives based on personal experiences.

Has the structure of the course evolved or changed since it started?

Whitehorn: “We still teach the basic components…we still teach what race is and how it impacts the world we live in and then understand how we got here. There is a huge emphasis on the past but how the past affects now. The books and articles have changed and the curriculum is updated.”

Mackercher: “Tonya, Kay, and I have worked together since the beginning. When she [Ms. Kay Wade] retired, I thought I want to follow the same lead with the history curriculum and I still consult her today. We do shift and change the curriculum as time goes on.”

How is the history and literature combination different from a traditional classroom setting?

Whitehorn: “When we sat down to write the curriculum, we figured out what big themes we wanted to cover. It is team taught so I know what Kathy is doing everyday and she know what I am doing everyday and it focuses on that particular theme. So, if we are talking about the Great Migration, we pick 5 overarching themes and then decide the curriculum based on those themes. Perspective is everything and shapes the course. The students are given a lot of voice. Very rarely do we lecture for more than 30 minutes.”

Mackercher: “One is that [the subjects are] integrated and we also bring in things like the arts or a sociological study. We are trying to take the social sciences as a whole and look at whatever topic we are talking about. Also, it’s definitely more at a collegiate level. We have brought in speakers that we have seen or heard from and will bring in their work. We have incorporated Dr. [Hasan Kwame] Jefferies’ online lecture series as well as Dr. Joy DeGruy into our curriculum. We are way more project-based with a lot of solid writing assignments and of course we have the show, but that’s not the only thing we do.”

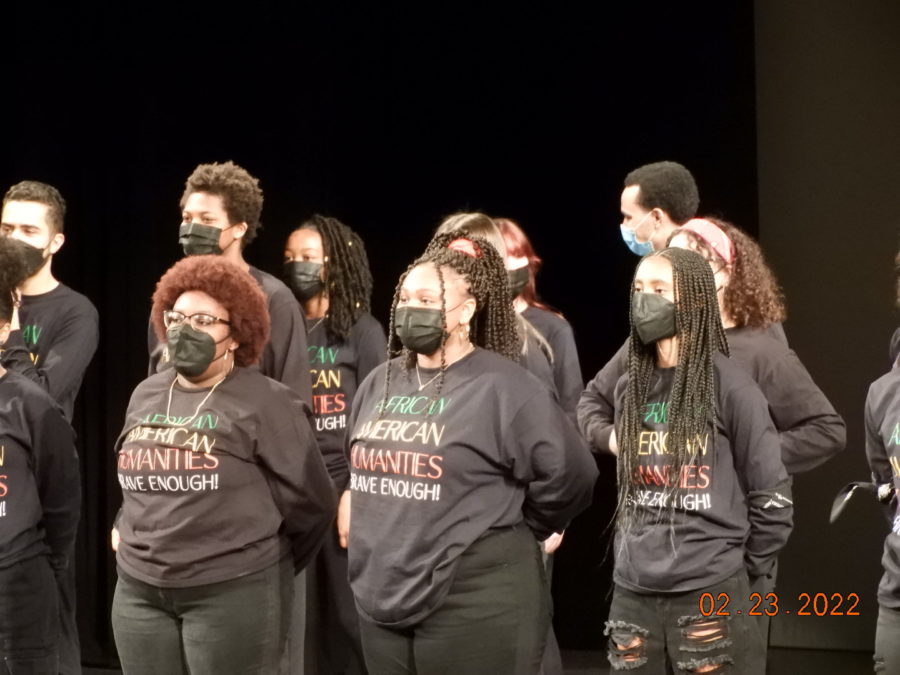

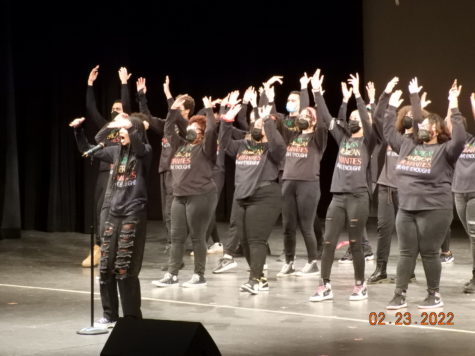

How does the show or performance play a role in the class?

Wade: “The show is unique to Skyline and was designed to apply what students have learned by creating, planning, and producing a performance that would educate and uplift. The choice of when to do the performance was deliberately chosen to be close to MLK day and Black History Month.”

Whitehorn: “Without the class, there would be no show. …A lot of African-American History is trauma-focused. We speak to remove the shame of enslaved persons and give respect to their ancestors. We also address the triumph. We don’t focus just on trauma, we focus on our ability to overcome everything and that you’re still standing.”

Mackercher: “I think for it to be a culminating event, it’s phenomenal in several ways. One, as a teacher, you definitely know whether or not they learned the material. But for them to be able to share it with their peers, their friends, their families and demonstrate how much knowledge they have gained in that unique way, I think is phenomenal. As a class, it brings them together and to see the bond, it’s so solid.”

What do you see as the future of the class?

Wade: “African American Humanities will continue strong. Ms. Whitehorn and Ms. Mackercher are doing an excellent job in continuing to make the course relevant and exciting. I would love to see the model adopted in more schools. I am realistic, though. We know the challenge that misinformation about the Critical Race Theory presents will slow the process down.”

Whitehorn: “My vision is that there is still a thirst for knowledge. One day maybe African American Humanities won’t be an elective along with other people’s history. I want to see more courses like this course and more students taking the course.”

Mackercher: “I would like for us to actually travel. I’d love the class to actually go to the West Coast of Africa and to learn history in person there and to have students in 9th and 10th grade have the basis and understanding African-American history.”

For students outside of the class, what are steps they can take to be more open?

Mackercher: “I think it’s important to immerse yourself with people who you normally don’t hang out with, peer groups or a particular game or event. I think that the reality is those who don’t want to be open, don’t do that. I’m not sure that there is always an answer for that but the first step is to put yourself out there and be authentic. It’s to show that those of us that believe or have different beliefs are present and want to learn from others. We hope by fostering a collaborative culture, other people will come along and join the community.”

Whitehorn: “Examine the things that they have been taught and examine the challenges to their beliefs. And if you believe one thing about an entire people, why is that? The biggest thing that I would tell students here is to question. No teacher…would be offended by questions. Just don’t be accepting of everybody and everything because that’s dangerous because you create these figures of people where people require your loyalty and you’ll never satisfy that person. It’s impossible. I want the kids that are enrolled in this class and the ones who are not in this class to be thinkers. Be open and accepting to other thoughts. Be thinkers.”