Skyline’s Lost Salamanders: The Forgotten Wetlands and The Fight for Restoration

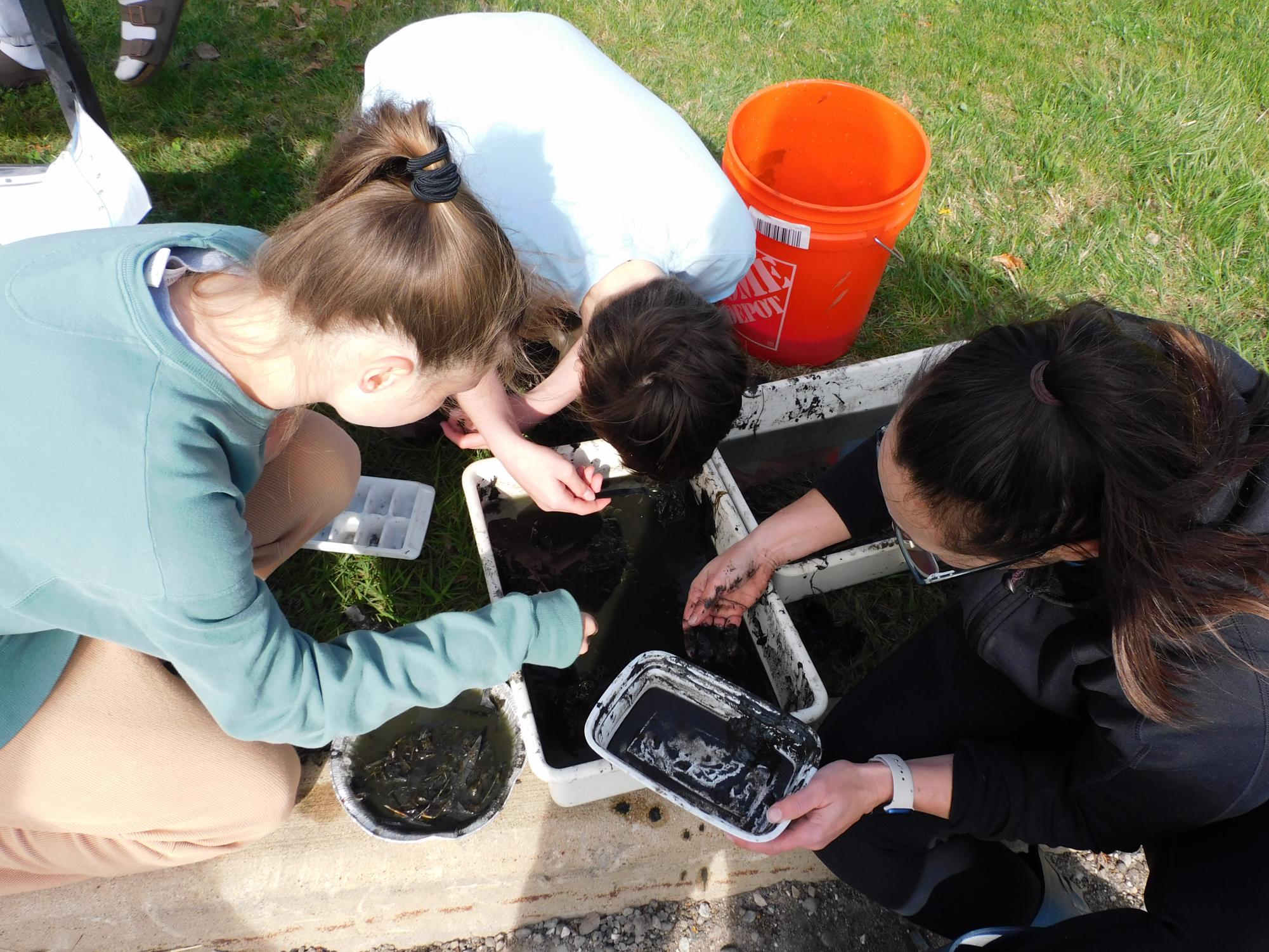

Every year, Skyline’s AP Environmental Science (APES) classes go salamander hunting. The group has heard too much about the school wetlands’ rare, “endangered” salamanders to not investigate for themselves.

The students, scattered in groups, are armed with nothing more than a phone camera, sketching tool, and a sharp eye. They loop around the school’s woods and wetlands, eyes scouring the ground, dodging poison ivy, and flipping over rotten logs in hopes of a glimpse of the rare creatures.

Their assignment is straightforward enough: create a nature journal, observe the environment, record biotic and abiotic factors. Yet, there is an unofficial goal: find the elusive salamanders. Spotting one would be the crown jewel among any other observations.

Nature journals quickly fill up with hasty notes, sketches, and photos—food webs, grasshoppers, limestone, Black-Eyed Susans, Coneflowers, deer prints pressed into mud—but rarely a salamander. “We were told by our APES teachers that there might be salamanders out there because of the fact that Skyline was built where the salamanders used to live. But my groups were never able to find [any],” said Elsa Wenzlaff (‘26), past APES student. “We looked on logs and in the forest near Skyline. And we looked for long periods of time, but mostly just found tiny little bugs.”

The annual search raises more questions than it answers.

“Weren’t these salamanders like an integral part of our community at one point?” Mona Spiteri (‘26), a past APES student, wondered aloud. “What happened?”

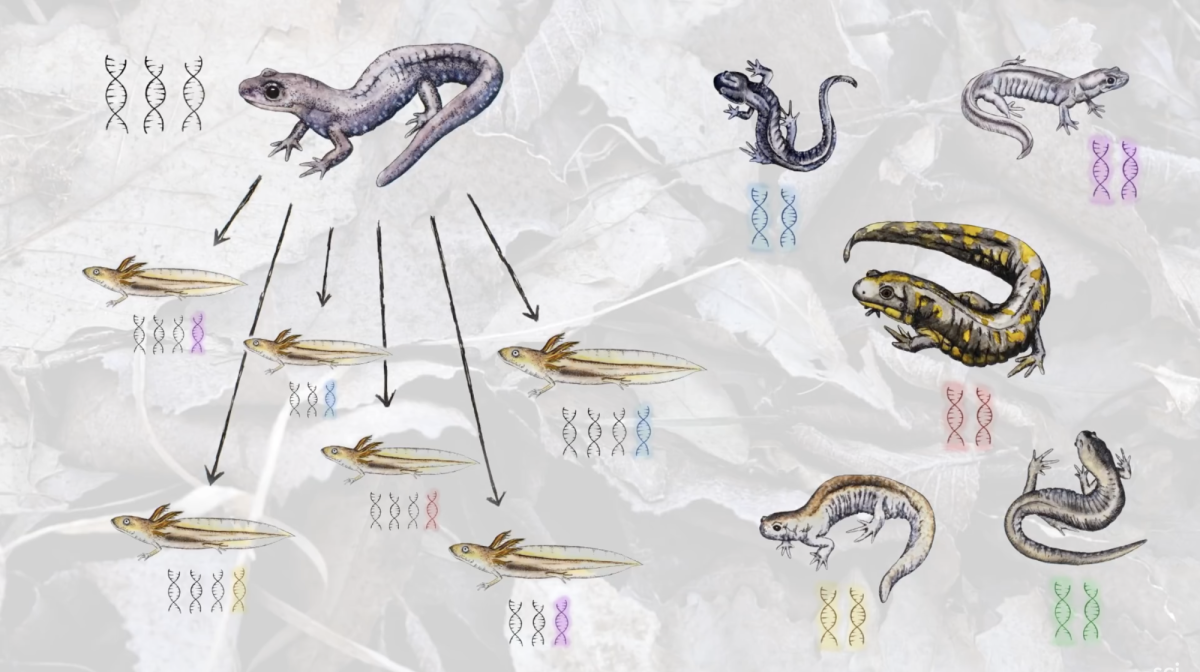

When construction for Skyline High School broke ground in 2004, it revealed a rare population of LJJ unisexual hybrid salamanders (first incorrectly thought to be “Silvery Salamanders”). Reports do not indicate who discovered them. The habitat supported the only confirmed location for the unisexual hybrids within the state of Michigan during this time.

The salamander finding raised concerns of local families and organizations about the impact of the building on the local salamander population and the health of wetlands. “The opening of Skyline was actually delayed by a year in part because they found a salamander on the property that they thought might be an endangered species,” said Casey Warner, Skyline APES teacher.

But it was soon discovered that due to the salamanders’ unique genetic makeup, they weren’t actually classified as a species and therefore not protected under the Endangered Species Act. To read more about what makes Skyline’s salamanders special, read our companion article here.

Even though they weren’t an endangered species, their rarity in Michigan prompted a wave of conservation efforts.

In 2005, following a comprehensive report conducted by Natural Area Preservation (NAP) on the area, an intensive amphibian and reptile rescue was launched. NAP created mitigation wetlands to replace the original one destroyed by construction, intended to provide a new habitat for the approximately 3,000 relocated amphibians (200 of them salamanders).

The effort led to the collection and relocation of over 5,000 individuals, representing 14 species in all life stages.

After the restoration work was completed, NAP received five years of funding to study all species on the Skyline wetlands. NAP’s head herpetologist, David Misfud, put together yearly herpetological/wetland survey reports from 2002 to 2007 (with a focus on the salamanders). This included monitoring species to assess the construction’s impact, regular walks along the fence during the first rainfall of spring to collect and relocate salamanders to the new wetland, and evaluating how suitable the habitat was for its new residents.

Funding for restoration efforts expired in 2008, and Misfud also left the project around this time. Since then, there’s been very limited monitoring.

Skyline’s natural areas have seen their fair share of neglect in the last few years.

The black fence installed around the property, meant to protect salamanders from traffic, has seen better days. “They put that fence up because salamanders were trying to come back to the pond. I’ve heard rumors that they got as far as inside the door,” said Hammond. “It’s very sad.”

When trees fall on it, occasionally APES students or other volunteers will move the debris, but there’s no money available for proper repairs or maintenance. Many students now simply hop over the crumpled fence to enter the area.

In addition, there is a broken pump that was used to pump water into a pond that maintained water levels for salamanders. After a tree fell on the pipe connecting it to the well around 2010, the pump has been inactive and no efforts have been made to repair it.

“At this point, it’s possible that the groundwater where the well taps into is contaminated from the dioxane plume,” said George Hammond, NAP Field Biologist. “I’m keen to get that fixed.” But due to the lack of monitoring and attention, the pump remains broken and the contamination status remains unknown.

The 2006 herpetological survey report identified continued monitoring of the Skyline wetlands as “imperative to measure the success of the site” and essential to species survival. The report recommended that “every possible effort should be made to maximize the education aspects of this site while concurrently being the best stewards of this area. A detailed and comprehensive management plan for this site should be developed, including placement of trails, habitat restoration, environmental education and stewardship opportunities, and long-term monitoring.”

The lack of continued monitoring has caused Skyline to face a major invasive species problem. Invasive, non-native species pose significant threats to ecosystems and biodiversity. The later 2008 herpetology report noted that “treatment is highly recommended to control these [invasive] species when concentrations are low and control is quite feasible. Management is most critical during the first three to five years of mitigation wetland development, as native plants become established and increase their coverage within the wetlands.”

The invasives that only began to grow in 2008 have spun out of control due to a lack of proper management. Now, non-native plants like honeysuckle, Japanese barberry, olive trees have run rampant at Skyline. Control has gone from feasible to difficult.

Managing invasive species requires significant resources and ongoing efforts. Advocates like Warner have pushed for AAPS to conduct a controlled burn of the area, but efforts have been slow moving due to funding. “Anything [we] could do would be better than nothing,” said Warner. “I just went in over the summer with a hacksaw, and just chopped away at a few [invasives] around the edges, but one person just going in there whenever she has time isn’t gonna [do that much], so we really need a burn.”

Warner contacted Mike Appel, local environmental restoration contractor and owner of Appel Environmental Design to get an estimate for a controlled burn that could mitigate the invasive species problem. “Prescribed burns are often challenges to give a price for, as there are many variables,” said Appel. “The interior of the [Skyline] woods in many places is quite nice with few invasive species, while many of the edges show significant encroachment by invasive plants, especially shrubs. Any of the wood’s three edges could also be burned as a smaller section for as low as $1200.”

In 2023, Warner applied for and received a mini-grant ($400) from AAPS and the City of Ann Arbor Office of Sustainability and Innovations to buy a wheelbarrow, gloves, and mulch to help prevent tree trunks from being damaged from the lawn mowers that mow around Skyline.

The next year, AAPS also removed a diseased oak tree infected with “oak wilt” from the Skyline woods to prevent the spread of fungus to other trees and the death of more oak trees in the area.

Besides these instances, there is no current ongoing research or maintenance related to the wetlands funded by AAPS. AAPS Communications Director, Andrew Cluley confirmed that “the district does not have any projects scheduled that are anticipated to impact this area around Skyline” but “remains committed to the environment including the woodlands and wetlands on the grounds around Skyline High School that are home to salamanders.”

Limited involvement from AAPS doesn’t mean others haven’t attempted to maintain the wetlands and to collect data. Since 2010, NAP has conducted volunteer species surveys at Skyline. However, these surveys are not quantitative and don’t allow for direct comparison of data from different years, as they rely mostly on the skill of individual volunteers.

“We just send volunteers out and say, ‘go look for salamanders; here’s where to look and here’s a little basic idea of how to look,’” said Hammond. “But we don’t control the amount of effort that they do. So, if we get a really good salamander finder one year, we might get a much higher number than the year before and the year before that because that person just finds more salamanders. And before that we had slack salamander scouts who found like two. Maybe there were 30, maybe there were two. We don’t know.”

Another complication, according to Hammond, is that NAP is funded through a particular tax that can only go towards improving and maintaining the city’s parks and natural areas. Because school district property is not part of the city’s parks system and is an independent, non-city owned environmental area, NAP is limited in how much it can directly intervene. “We have to be careful about how much we do for off-city problems.”

AAPS’s District Sustainability Policy, adopted in 2022, includes a goal to “maintain and enhance outdoor environments on AAPS campuses” in order to provide outdoor learning opportunities.

This goal can only be truly realized if Skyline’s natural areas receive the attention and care they need. While educational efforts are undoubtedly very important, so is the preservation of land AAPS owns, especially as organizations like NAP must limit their involvement with school-owned properties. The health of our wetlands and the safety of the animals that live within are at risk.

The Skyline wetland is more than a patch of muddy land: it is a living classroom, a habitat for rare wildlife, and a significant part of Skyline history. Yet, without adequate funding and regular monitoring, important resources risk becoming dangerous by potentially harboring unmitigated toxins, overgrown with invasive species, weakened by damaged infrastructure, and ultimately forgotten.

If you care about Skyline’s natural areas, there are ways to make a difference. Get involved with groups like NAP, volunteer with your local community science efforts, and advocate for increased funding for environmental preservation efforts. By working together, we can restore these lands and make sure that this habitat remains a valuable resource for students, wildlife, and our community.

Here are some ways to get involved with local community science efforts below:

Your donation will support the student journalists of Skyline High School and help us cover our annual website hosting costs!