The term cringe has exploded beyond its dictionary roots. No longer just an involuntary reaction to discomfort, “cringe” has become a cultural label, a weaponized buzzword aimed at policing sincerity, enthusiasm, and emotional vulnerability.

Cringe culture refers to the online (and increasingly offline) phenomenon of shaming people for being earnest, awkward, or unabashedly embarrassing. The umbrella of cringe encompasses many categories. It’s the ridicule of teenagers who roleplay on TikTok or know all the words to Hamilton. It’s the face you make when someone calls their teacher “mom” in front of the whole class. It’s crying too hard during a concert. Liking a ‘bad’ show. Writing angsty poetry. It could be existing in a body that’s not conventionally attractive and daring to post it. It breaks the social contract of cool.

I’m not arguing that we should shield people from criticism when they’ve done something harmful or problematic (like Colleen Ballinger’s much-memed ukulele apology). There’s a very distinct difference between calling out problematic behavior and just punching down.

My problem with cringe culture is that it targets the harmless.

Psychologist Carl Jung once said, “Everything that irritates us about others can lead us to an understanding of ourselves.” Maybe we, too, once sang with too much enthusiasm, raised our hands a little too fast in class, liked something too earnestly – and were punished for it. Now, we censor ourselves in the fear that we’ll get picked on for it, while simultaneously doing the same to someone else.

In online spaces, this phenomenon is only amplified tenfold. Under the comfortable mask of anonymity, users have no problem picking issues with any behavior they think is irregular. Entire online accounts are dedicated to clipping random videos and reposting them to a pack of ravenous commenters, ready to rip people apart.

Phrases on TikTok like “this is the original” or “what is this referencing?” are often code for “this video is so cringe, it’s destined for parody.” Creators who create videos mocking cringe behavior are quick to reassure any confused commenter that of course, their video isn’t the original. It’s a parody – a performance! The maker could never act this way, not for real.

These mocking content creators rush to distance themselves from the behavior they’re mimicking. Everyone is in on the joke – everyone, of course, except the person being parodied. These videos serve as a reminder of what not to do, of who not to be. The audience derives pleasure from the fact that they are not cringe – at least, not as outwardly embarrassing as the people being mocked.

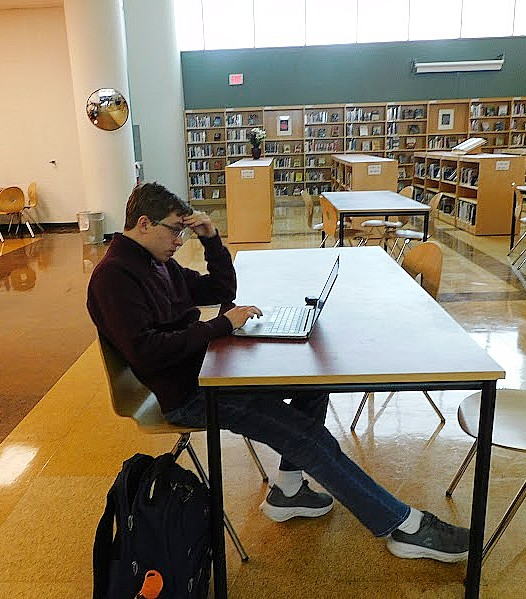

I remember being a freshly-minted 6th grader, so ready to leave the childish whims of my elementary school self in the dirt. I was eager to be cool, to denounce many of the interests and actions I had enjoyed just months prior. Everything was embarrassing to me (and sometimes still is) because being a tween is a strange, awkward, embarrassing age to be.

I used to like Gacha Life, Nightcore, and all manner of childish, embarrassing YouTube videos. I would sing loudly and unabashedly (more times than not out of breath and out of key) around the playground, cringe more times than I could count. But when I saw others doing things I once did unironically, I became a silent judge.

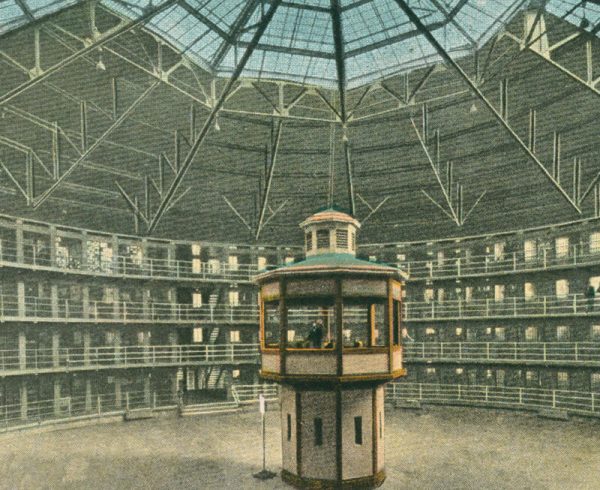

Cringe culture functions like a digital panopticon. In philosopher Michel Foucault’s reinterpretation of Jeremy Bentham’s prison design, the panopticon is a circular structure with a single watchtower at its center. Prisoners never know when they’re being observed, so they internalize surveillance and begin to police themselves. Over time, the fear of being observed becomes stronger than actual observation. At some point, the guards don’t need to say anything – there might not even have to be any guards in the tower at all, because the prisoners regulate themselves.

Under cringe culture, we’ve become both prisoner and guard. We observe the world with one eye on ourselves, rehearsing every action, every post, every facial expression through the strict lens of how it might be received.

But here’s the truth: to be cringe is to be free. To feel deeply, to act without irony, to love something openly and unabashedly – that’s freedom. To reject cringe culture is to reclaim agency over your own life.

Cringe is not the enemy. Shame is. Cringe culture has taught us to laugh at the parts of ourselves that feel too much – which can be a valuable lesson.

If you want to truly live, you must be cringe. So go ahead! Wear that cosplay. Make that fan edit. Cry during that concert. Start that Minecraft YouTube channel. You’re cringe – that’s the whole point.