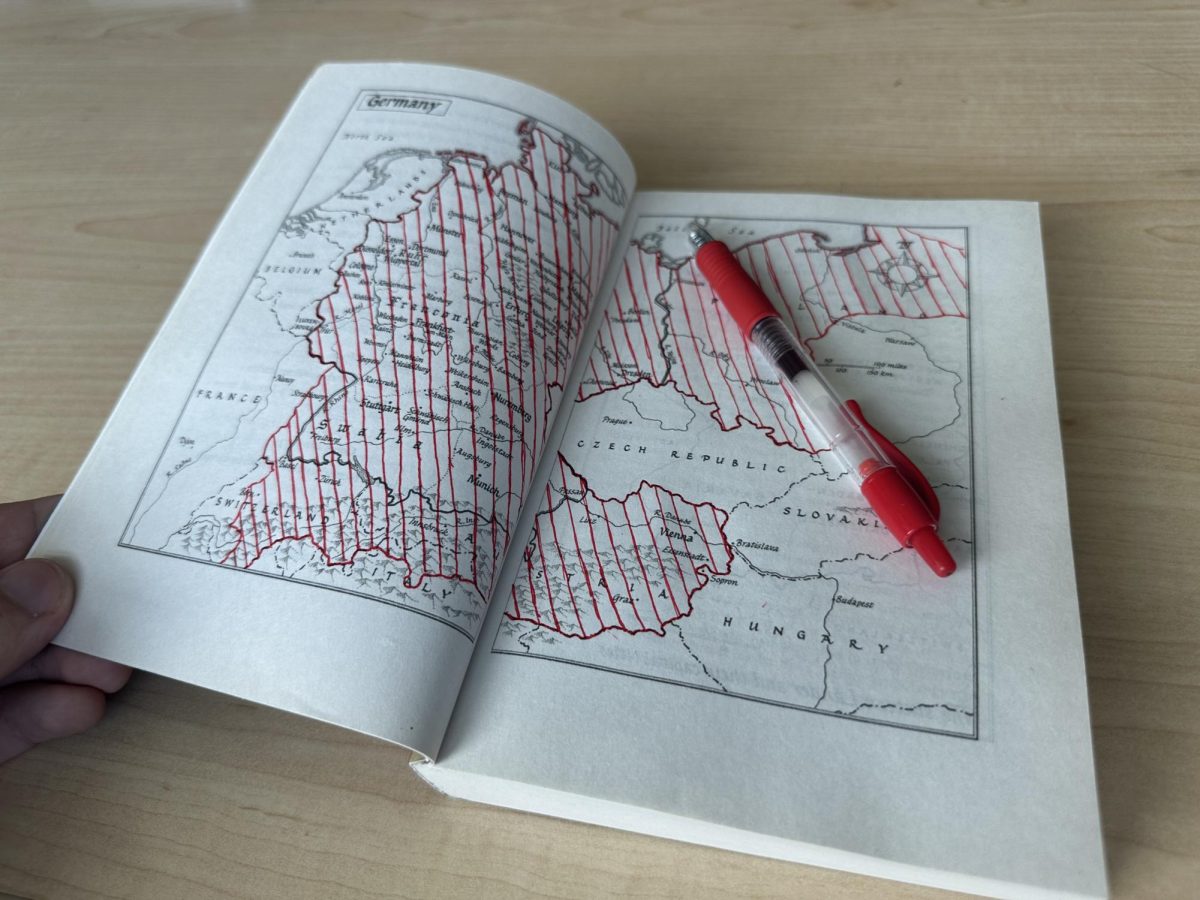

Simon Winder’s Germania: In Wayward Pursuit of the Germans and Their History (Picador, 2011) believes the most important part of German history is Adolf Hitler. It is a history book about something its whole premise is to ignore and a worse-than-useless resource — it teaches people not to care about what its supposed subject is.

Germania’s premise is pure-hearted: to explain the entire history of the area now named Germany until 1932, the year of Adolf Hitler’s promotion to power. With that boundary, the book intends to accentuate the better parts of German history, and the parts of German history which “the Nazis buried and ruined and [which] so many Germans have since worked to rebuild.” Instead of genocide and gas chambers, Germania wants to talk about castles and kings.

There is, however, an issue with that premise. German history is not all castles and kings, not even nearly. By stopping at the Nazis, Winder implies that they are an abnormality, and that although their reign of hate was evil, it was also an outlier if you look at the whole of the history.

That notion is entirely untrue, though. Hate is as integral a part of German history as any other, and to imply the Nazis weren’t a culmination of that hate is far from honest. From the Rhineland Massacres of the People’s Crusade to the banishing of Jews from Silesia, German history is filled with moments of hatred unrivalled in their brutality. These moments may not be on the same scale as the Third Reich’s industrialized violence, but their viciousness is undoubtedly equal to it.

But a book with a failing premise is not necessarily a bad one; the real failing of Germania is that it fails to even stick to that premise. For a book that means to highlight the good of German history, it seems overly obsessed with the Nazi regime.

Every chapter contains a reference to the Third Reich. “Hitler drew at least as much inspiration from the British empire as the Roman,” Winder randomly writes in a section supposedly centered on German antiquity, “wishing to treat the Slavs as the British had the inhabitants of India, although he ultimately treated them as the British had the Aborigines” (28).

“Instead, all that the Emperor got as compensation was a small chunk of near empty agricultural land along the River Inn,” he says in the epilogue to his retelling of the War of Palatine Succession, “thereby later on giving Austria the opprobrium of being Hitler’s birthplace, with consequences too complex and sickening to muse on” (207).

For a book about any part of German history other than the Nazis to continuously reference those 12 years implies they are the only years worth referencing. It gives the reader the idea that the most important years of German history are the years wherein all of its worst aspects were on full display.

German history is confusing and contradictory, as all history is. It is beautiful and ugly, wonderful and terrible, joyful and tragic — and, above all else, complicated. Germania, however, does not believe so. It believes German history is simple, and is best summarized in the years 1934–1945.

With the German far-right’s recent electoral victories, Germania’s assertion that the Nazis epitomize the country’s history are worse than unhelpful — it is harmful. If a country’s nature is fascistic, then what point is there in opposing those who try to implement fascism?

This is obviously, intrinsically untrue; Germans are no more predisposed to fascism than any other people, and those who want that to change must be stopped.